I’ve known that I’ve had arthritis in my knees for a long time, about thirty years. This year, my knees finally caught up with me and I’ve already had one total knee replacement and am due to have the next one in a few days time. In the past few months, I’ve met so many people who have had knee replacements that it’s very clear that this is quite a common thing. However, I thought I’d record my experiences and thoughts on my knees, just in case it might be useful to someone. I hope you never need a knee replacement, but if you do, you have my best wishes and support.

The first signs

It was in my late twenties that I first noticed something was wrong with my knees. When playing golf, I started to notice that I couldn’t completely squat down to line up a putt like I used to. This gradually got worse but I didn’t think much of it. In my early-mid thirties, I first went to an orthopaedic surgeon to get checked out. I was living in Singapore at the time and the surgeon quickly had the appropriate scan organised. He just briefly looked at the scan and said “Ah yes, you have arthritis in your knees. You will need knee replacements one day, but wait as long as possible. No running!”, and that was basically it.

What made the arthritis appear so quickly

After talking to lots of doctors over the years, I think I’ve found what accelerated my arthritis and made it become significant at an early age. When I was in my twenties, I did a lot of running and was into powerlifting. The worst exercise for the knees in powerlifting is the squat. I got up to doing a 500 lb competition squat in my mid twenties. My latest surgeon tells me that this running and powerlifting didn’t cause my arthritis, but it accelerated it.

With arthritis, the cartilage between the bones disappears over time. The cartilage acts as a cushion between the bones and, as it disappears, you start to get bone coming into direct contact with other bones in the joint. Now the body panics as the bones aren’t meant to carry our weight directly like this, and the bones of the joint actually grow extra bits (osteophytes) so that there’s more surface area to spread the weight over. As these extra bits grow in size they can actually stop the joint from moving as it should (might not fully straighten, might not fully bend, will often cause clicking sounds and can even lock the joint in one particular position) and will eventually start aggravating all the soft tissue around the joint causing continuous pain. It’s not a pretty result and it all comes from the body trying to carry your bodyweight with bones resting directly on other bones.

This is why the doctor told me not to run. Anything that increases the pressure between the bones in the joint will cause the bones to grow the extra bits more rapidly and hence bring on the problems of arthritis faster (for those not prone to arthritis, running cause some damage to the cartilage but this repairs itself with rest and recovery). Running creates 5-8 times your body-weight through the knee joint. I can’t imagine what the powerlifting squats were doing. Just doing normal squats puts 7-8 times your body weight through the knees, but with 500 extra pounds on my shoulders, argh! My poor knees.

The surgeon in Singapore didn’t tell me about digging. I only learned about this in the UK. Digging in the garden is very bad too. It causes much extra force to go through the knee joint and accelerates the problems of arthritis. I wish I’d known that 15 years ago!

Managing along with my knees

From my early thirties through to my mid-fifties, I managed to get by with my knees. I didn’t do any running. For sport, I mainly did golf, walking and skiing. When I moved to the UK (late 2014), I started to get into gardening quite a bit. I was doing things that I thought would help me get fit, but I was actually back in an arthritis accelerating phase without knowing it. It was common for me to be digging holes to plant trees in our garden and to be wheeling very heavy wheelbarrows up and down our sloping property. Digging puts off lot of extra pressure into the bone-on-bone knee joint, especially when the digging is hard and there’s a need to “jump” on the spade. The heavy wheelbarrows likewise put a whole lot of extra pressure into the contact between two bones.

I wasn’t aware of it, but I was making the arthritis progress more quickly with all this heavy garden work that I thought would be good for me. It was a phase of about six years of heavy garden work before I realised what was happening. The doctor in Singapore (when I was in my thirties) said “No running!” and now the doctor in the UK said “No running and no digging!”. Oh, how I wish the Singapore doctor had added the “no digging” part.

When to go for knee replacements?

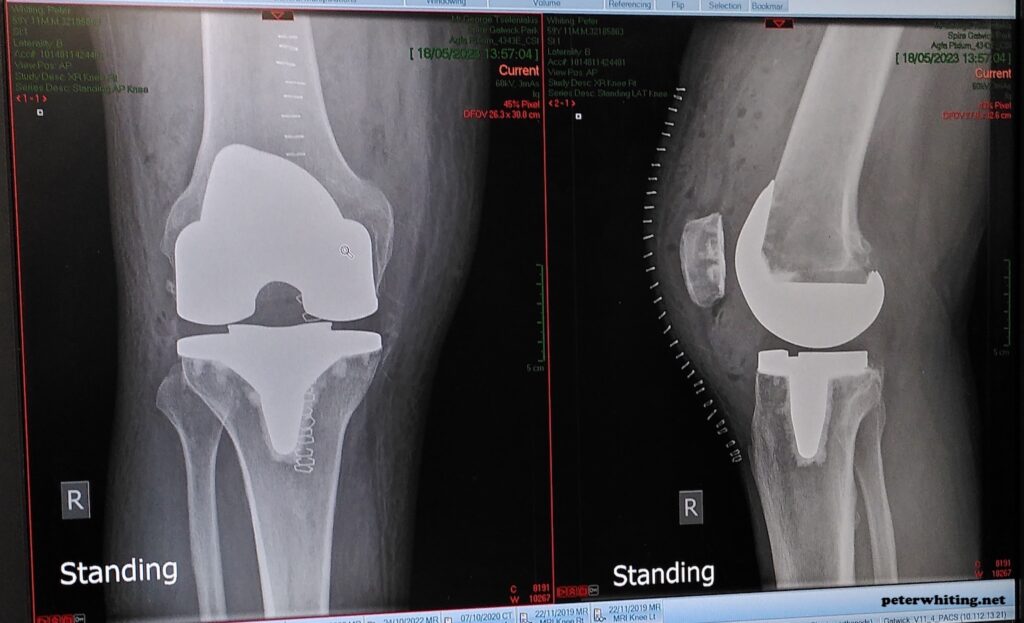

My surgeon in the UK told me he never recommends for someone to have a knee replacement, he waits until the patient says it must be done. When I first saw this surgeon (about 5 years ago) and he was looking at the MRI scans of my knees, he said that I had “very severe” arthritis. I asked him that if he didn’t know me and was just looking at the scans, how old would he think I was? He said he didn’t like making such estimations but since I asked, he said late 70’s. I was 55 at the time.

Another reason to wait as long as possible for knee replacements is because they don’t last forever. After about 15 years, they need a “revision”. Having said this, I’ve got to know several people who have had knee replacements 20 or more years ago and they’re still going strong.

So, I decided to avoid running, digging and heavy wheelbarrows and try to last as long as possible on my arthritic knees. Of the activities that I really like to do, skiing, is one that puts a lot of pressure on my knees (but at least no jarring!) and, every time I went skiing the pain would get quite bad. Luckily, the surgeon prescribed me Naproxen (similar to Ibuprofen but long-lasting and maybe more powerful) for my ski trips. This helped a lot. I was able to keep skiing and, even though my knees were painful, it was (mostly) tolerable.

As the years went on, I started to find climbing stairs more difficult. It was painful. Walking long distances through airports too. A lot of things were starting to get more and more difficult.

The final straw

Finally, it was a skiing trip in January this year (9 months ago) that proved to be the final straw. I skied on 13 days on a 2-week holiday. Everyday, my knees were painful even though I was taking Naproxen. There were days where I thought that I had to have a rest day and stayed in the chalet, but then I saw the sun and the snow outside and put my skis on anyway and went for a ski.

Driving home from the ski trip (France to the UK), I found that my right knee and leg was constantly too painful to drive and my wife had to do most of the driving. I thought that the pain would calm down after I got home and rested for a few days. It didn’t. The pain stayed constant, not just in my knee but in my whole leg – calf, shin, hamstring and quadricep, and even in my hip. My leg was constantly bent and there was no way I could straighten it.

So, I ended up having another MRI to see if anything bad had happened. One of the things that could have happened is the one of the bits of extra bone (osteophytes) grown through arthritis, also called bone spurs, could have broken off and wedged itself somewhere. The scan showed nothing like that but it did uncover incredible inflammation of all the soft tissues around the knee and going up and down the leg. I heard the surgeon say quietly, almost to himself, “you really need a knee replacement”.

After this scan, knowing that nothing super serious had happened inside my knee, I decided to give it some more time and see if the inflammation settled down. I waited one month – no improvement. Waited and rested my leg for another month, again no improvement, but worryingly, the pain start to get worse. It was getting worse and worse, so I met again with my surgeon and said that it’s now time.

Prep for the operation

My operation was scheduled for May. Here’s what my surgeon told me to expect. He said, “For the first six weeks, you’ll hate me because of the pain. Up to 5 month afterwards, you might think you’ve made the wrong decision, but after 5 months, you’ll be feeling good. The recovery process will go on for 18 months. After 18 months, there will be no further improvement in the range of motion of the knee”.

Before the operation, I had to see physiotherapists a couple of times. They want to make sure that you can use crutches properly, in the way that will be necessary after the operation. It’s quite easy to go up and down stairs with crutches as long as you know the tricks. Also, there are a bunch of pre-operative exercises to do before to help improve the recovery speed after the operation.

The operation (and waking up)

For the operation, they use a spinal injection to numb me from the waist down and then a mild sedative gas to keep me under. That’s all fine, but I had the bizarre experience of waking up during the operation. If somebody had told me this would happen, I would have freaked out, but it was ok actually. I opened my eyes and there was a fabric screen in front of me. I looked backwards and my anesthetist was sitting there. I said “I’m awake!” and he said “I know! I had to wake you up because you were coughing”. Then I realised that I could hear some incredible banging and drilling sounds, as if I was in a car garage. I thought that the noises must be the surgeons working on my leg (there are two surgeons for knee replacements), but I couldn’t feel a thing. Then I was under again. The whole thing would have been less than a minute.

Coming to back in the ward

Waking up in the bed in my room, there’s still no feeling from the waist down as the spinal injection hadn’t yet worn off. This was about 8pm. Feeling like I couldn’t move and couldn’t sleep for hours. The whole night actually. I had a catheter bag, so no need to get up for the toilet. All I did was watch terrible shows on the TV and put up with the almost continuous checks by the nursing staff.

At about 3am I was feeling restless, so I asked the nurses if I could get up for a little walk (I’d heard from the physios that the quicker you get moving the better for reducing scar tissue build up and speeding the recovery). The nurses helped me get of bed and I shuffled around a bit with the assistance of a walking frame. Walked out into the corridor and then back to the bed. Job done.

Forceful physiotherapists

There are lots of small physiotherapy exercises to do from the very start. On the second day after the operation, I was getting around on crutches instead of the walking frame. The bandage was off and just a simple dressing on the (long) wound held together with staples.

Before leaving the hospital, you have to clear a few tests with the physios. They take you to a room where you have to show that you can get up and down stairs and do a few other exercises. Then came the hardest part for me. You have to be able to demonstrate that you can bend the knee to 90 degrees. I was sitting in a chair and the physio lady asked me to bend the knee to 90 degrees. I couldn’t do it. She started assisting me by loosening up the knee and pushing it further than I could move it. It was quite painful and I said it feels like the wound might split open. She said “I know it might feel like that, but I can assure you that there’s no chance of it splitting open”. She kept pushing and we managed to get it to 90 degrees. I was happy about the success, but that was super painful. It was important because you’re not allowed home until you’ve bent the knee 90 degrees, and if you can’t do it, they put you on a machine that bends the leg and everyone says “you don’t want that!”.

Back at home

For the first four weeks, I’d say it’s all about pain management, trying to sleep and doing physio exercises. Even though I was on three different painkillers at the same time, the pain was hard to manage. It was hard to find a comfortable position in bed for sleeping, and getting a good sleep was really hard. It was also surprisingly hard to find a comfortable position for sitting. My leg was sore all the way up to the hip and I couldn’t sit on a normal chair or a desk chair because the edge of the chair created pressure on the leg that was really painful. The pain wasn’t just around the knee, but all way up and down the leg.

It’s very important to keep the physiotherapy exercises going as they make the recovery faster and more successful. These exercise took me about an hour each morning and evening and, for the first couple of weeks, I had to have someone help me with some of them. After a few days of being at home, I realised that the painkillers were not keeping the pain under enough control to allow to keep at the exercises. I called the hospital and spoke to my GP before It was decided to add liquid morphine to the mix. This did the trick, but I had to be careful to use this for the shortest period possible because of the risk of addiction. I only needed it for not much more than a week.

The first four weeks at home were the worst. All the exercises, difficulty getting up and down the stairs, trying to find a comfortable position for sitting, applying ice packs to the knee every two hours, remembering to take pain killers every few hours. Also had to go to see the physiotherapists each week at the hospital, which was quite interesting because they gradually change the exercises so that the strength of all the leg muscles progressively improve. I really had no idea how the muscles, tendons and ligaments worked around the knee but now I know a lot more, and I respect the physiotherapists for knowing how to build up, step by step, the strength of the leg again.

Between about week 4 and 5 after the operation, I was starting to feel more normal. I was able to walk without a crutch for short distances and I felt like I could get in and out of the bath safely (even though the physio’s thought this was too early). Still not sleeping well and really needing to have a nap in the middle of every day. Still very hard to sit in a normal chair comfortably (that took until about week 6 before I could do that on some chairs). Over weeks 4, 5 and 6, I scaled down the pain killers to just about zero. Things were looking good until I started to do a lot of walking for exercise.

The next step

As soon as you’re able, you’re encouraged to walk as much as possible to help the knee and leg recover. I was walking up and down our road as much as I could, twice a day. I gradually got up to about 30 minutes each morning and evening. Then I started to notice that my left knee (the one that was not operated on) was getting sore. This soreness got worse quickly and I was finding very difficult to walk home after about 10 minutes walking down our road. It was really weird – my operated leg was feeling strong and wanting to keep walking, but the pain in my left knee was stopping me. This was just getting worse and worse and it became clear that my left knee was having the same problems that my right was having. This was going to have to be fixed as well.

So, that’s where I am now. I’m waiting to have my left knee replaced in three days time. Not long to go now. The knee/leg has been gradually getting worse and worse. I was taking some painkillers so I could sleep and keep up with physio exercises, but they started to give me stomach issues, so I had to stop them quickly (or risk getting a stomach ulcer). For the past three weeks, I been using only paracetamol and generally just having to put up with pain and discomfort. I really can’t wait for the operation to be done.

From talking to the physiotherapists, I now understand the importance of keeping the leg as strong as possible in the lead-up to the operation. Not just strong, but also preserve as much range of motion as possible. Therefore, I’m doing about an hour of exercises and stationary bike work each morning and evening, plus exercise in a pool whenever possible. It’s very clear that my left leg is stronger than my right one was. Hopefully, this will make the recovery from the next knee replacement smoother than that of my first one. Fingers crossed!

Final comments

The recovery period for a total knee replacement is quite long. Soon after the operation, I noticed that the operated knee was quite warm/hot compared to my other knee. My surgeon said that’s normal and it will stay like that for 9 months. So far, it has been about 6 months since the operation and it’s true that the knee is still quite warm compared to the other knee. The knee feels very strong and I’m very comfortable with it, but it’s still obvious that it’s continuing to improve. It’s still recovering.

Another thing the surgeon told me was that I’ll be able to improve the range of motion of the new knee for 18 months. He said that after 18 months, there will be no more improvement possible. Currently, I’ve managed to get the knee almost straight (I’m guessing it’s only about 1-2 degrees off straight now) and it’s been very hard work to get it to this point, and I’m still working hard on it. The surgeon’s notes say that my knee had a 20-30 degree bend before it was operated on and it hasn’t been straight for many, many years, so it’s no surprise that it’s hard work to gradually convince it to straighten.

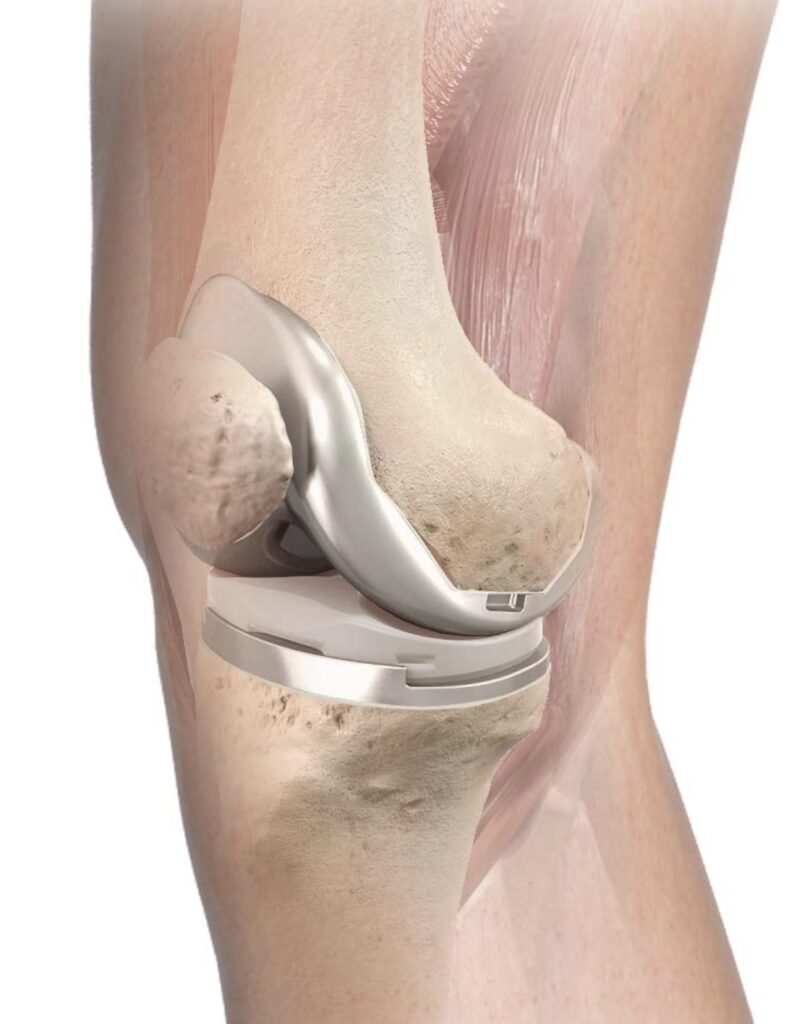

The other part of the range of motion is how far the knee can bend. The interesting thing is that the new knee has a limit of 130º of bend built into it. It can’t go further. I assume this is for stability and related to the fact that lateral stability is also built into the joints design because the operation actually includes removal of the two cruciate ligaments that give the natural knee lateral stability. Today, my knee can bend to about 115-120º and the physio’s are very happy with that. I’ll keep working on that too.

The new knee is a chrome alloy with a medical grade plastic in between. They have also reshaped my kneecap and lined it with medical grade plastic. It’s very interesting how my new knee has a better shape than it did before. More normal. When I look at my left knee and see the knobbly kneecap and the strange swellings, and when I feel the strange bone growths that arthritis has created around my knee, it makes me look forward fondly to getting all this repaired.

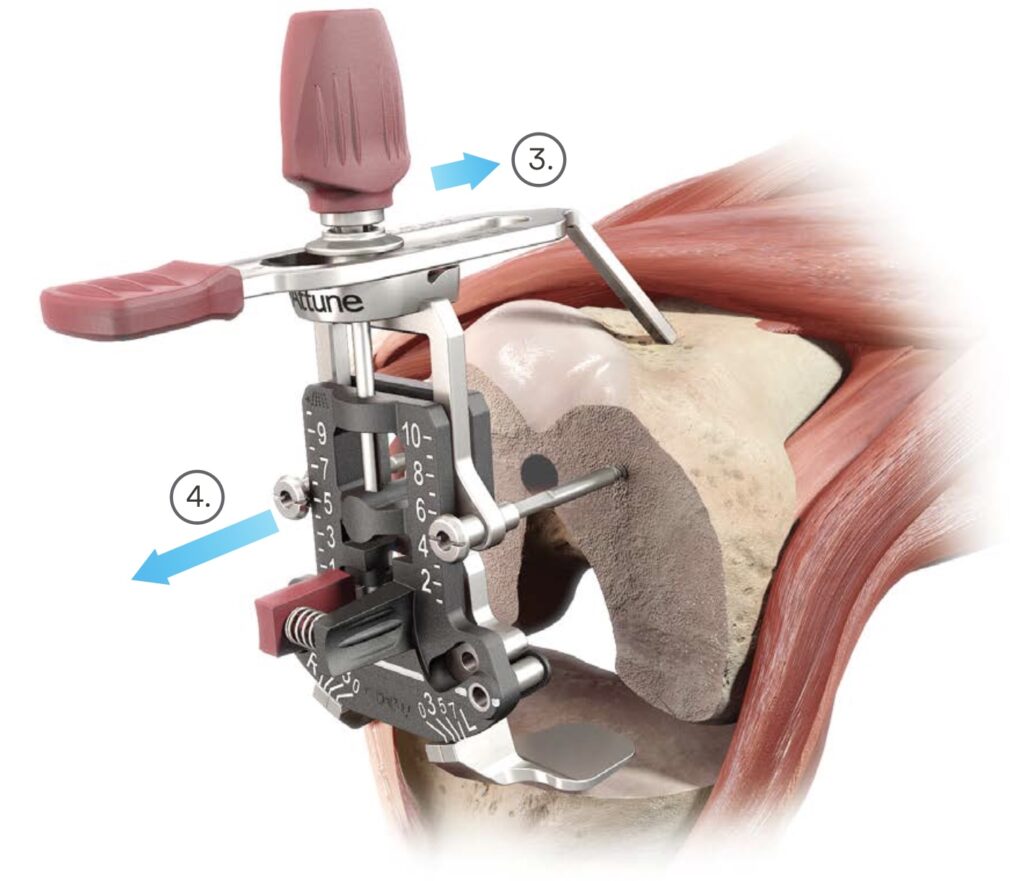

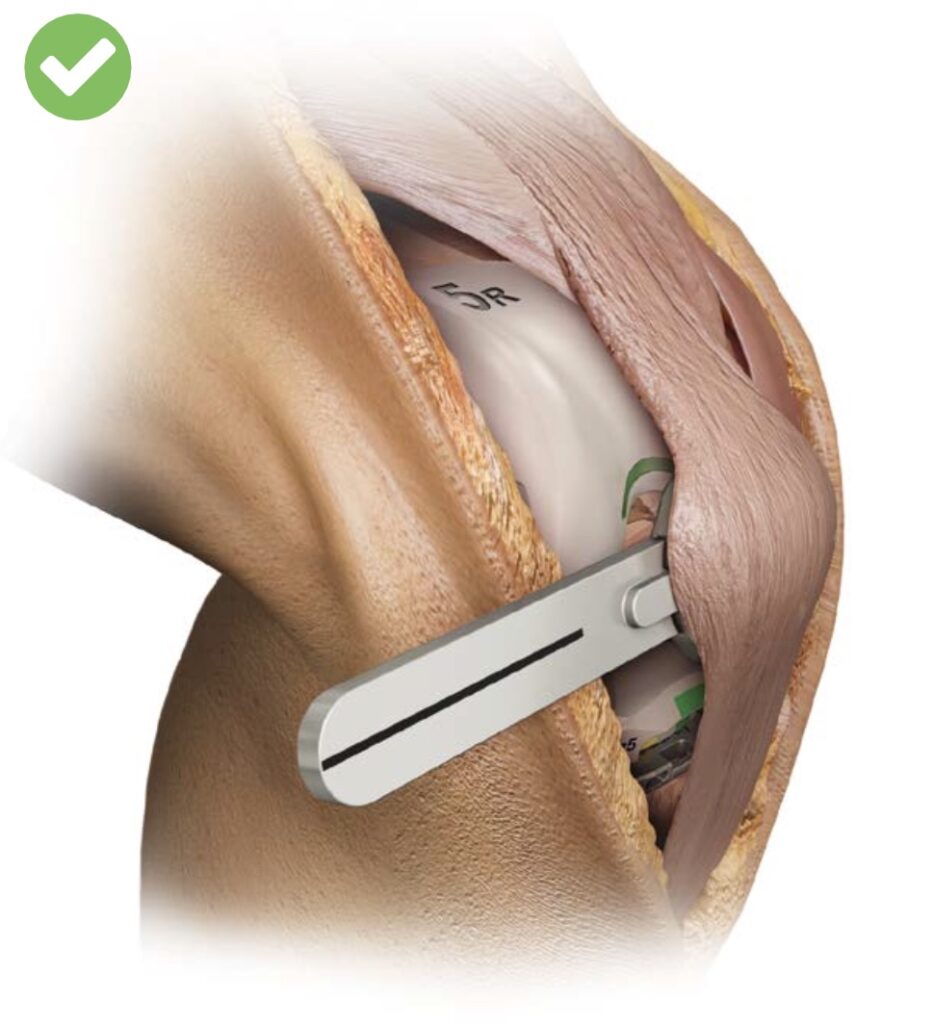

Below are some photos from the surgical instructions supplied by the manufacturer of the new knee. It’s a complicated, difficult and invasive operation. I acknowledge the skill of my surgeon for his fantastic work.

[…] year was the year I had both of my knees replaced (one in May and the other in November) and it was a year where I was very limited physically. For […]